- IN THIS ISSUE

- Main Page P1

- Two Champions of the Underserved Talk Shop PP 2–3

- A Fellow Gives Tips on Starting Your Own Practice P4

- Older Adults and the Opioid Crisis P5

- SAMHSA Attends Opioid Treatment Community’s Biggest Anuual Conference P6

- SAMHSA Is Always Looking for Peer Reviewers P7

- News and Views P7

- Professional Development Opportunities (Conferences, Calls for Papers, Trainings) P8

- The Systems of Care Approach P9

- Children With Serious Emotional Disturbance PP 10–11

The Systems of Care Approach Brings Together Services for Children, Families, and Communities

by Marla Fogelman

A

bout 20 percent of U.S. children have a diagnosable mental health condition. More than 5 percent1 have a mental health disorder that impedes their ability to function at home, in school, and in their communities. Because these children are often involved in multiple service systems, addressing their behavioral health challenges without coordination across systems has been shown to be financially burdensome for families, schools, and communities, and ineffective in providing these children with the comprehensive range of services they need.

That is why, since 1993, SAMHSA’s Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) has been committed to supporting the systems of care (SOC) approach for treating children and youth with serious emotional disturbance (SED) and their families. SOC refers to a coordinated network of home- and community-based services and supports that is also

“A system of care,” said Dr. Gary Blau (pictured above), who serves as CMHS’s Child, Adolescent and Family Branch chief, “is the overarching framework that provides a foundation for what a service array should look like” and represents a “paradigm shift from the one-on-one approach” that has traditionally been used in behavioral healthcare service delivery.

How the System of Care Concept Evolved

The need for developing a less fragmented approach to serving children with behavioral health disorders began in the early 1980s, with the publication of a national study that found that about two thirds of all children and youths with severe emotional disturbances were not receiving appropriate services.2 One reason for this finding, the study pointed out, was the lack of coordination among the various child-serving systems, and the limited resources provided to these children at national, state, and local levels.

In response to this issue, Congress in 1984 provided funding for a comprehensive program, the Child and Adolescent Service System Program, to serve children and youths with SED and their families. A decade later, in the early 1990s, Congress went on to establish the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children with Serious Emotional Disturbances Program, more commonly known as the Children’s Mental Health Initiative (CMHI). Since its inception, CMHI has provided funds for systems of care implementation to more than 300 state, county, territorial, and tribal grantees. CMHI, administered by CMHS, has also continued to receive bipartisan congressional support over the years, with appropriations ranging from $4.9 million in 1993 to $125 million in 2018.

The reason for this continued congressional support, said Blau, is because “there has been a robust national evaluation demonstrating that systems of care work. ” He added, “There are significantly improved clinical outcomes, improvements in school attendance and performance, less involvement in the juvenile justice system, and reductions in suicidal ideation and attempts.”

Why the Systems of Care Approach Works

In CMHI’s most recent Report to Congress,3 which analyzed the cohort of nine demonstration grants initially funded in fiscal year 2010, data were compared for children and youth served by the CMHI grantees at four different time points: a) 6 months before entry into the system of care, b) at intake, and c) at 6 and d) 12 months after intake. Findings from this evaluation showed significant improvements in the children’s overall functioning and that they were less likely to

Because SOC is effective in providing community-based services, facilitating meaningful partnerships with families and youths, and focusing on cultural and linguistic needs, the approach can be specifically tailored to the population being served. As Gary Blau said, “what may work in inner-city Chicago, may not work in rural Montana.” He also stressed that SOC helps children across all U.S. populations, including a particular focus on children and youth from minority and underrepresented populations, and on families whose income is below the poverty line.

Why Systems of Care Is

Especially Relevant to the MFP

The systems of care framework is consistent with the both the goals and values of the MFP in its emphasis on serving minority and underserved populations and in stressing the need for building a culturally responsive behavioral health workforce.

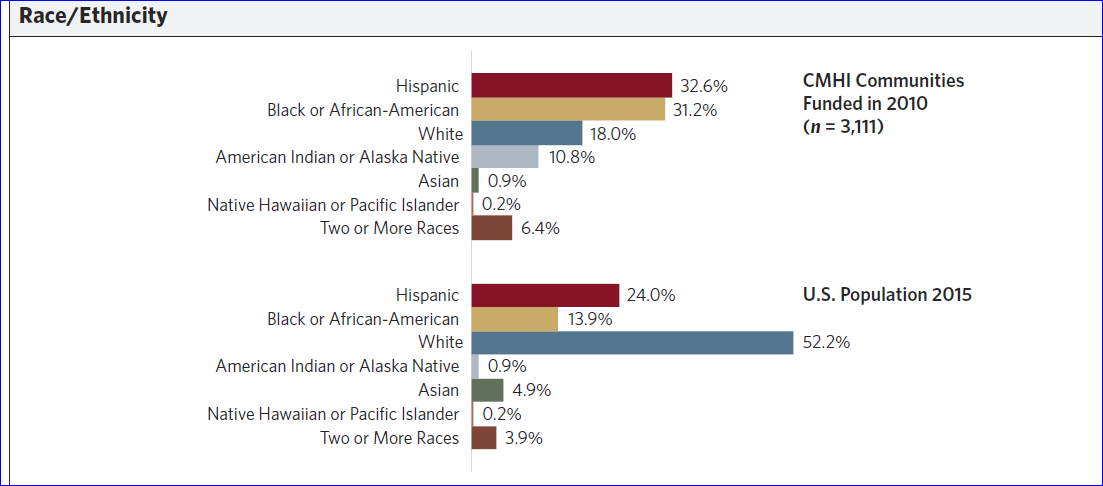

CMHI has been successful in providing SOC services to children and youths in populations who experience health disparities, including Hispanics, African Americans, and American Indians or Alaska Natives. For example, as shown in Figure 1, the percentage of black or African American children and youths served through a system of care was more than twice that of the children and youth in the general U.S. population.

In addition, in a 2012 study on American Indian and Alaska Native children and youth, SOC was shown to be effective in reducing rates of suicide attempts.4 Also, as indicated in The Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children With Serious Emotional Disturbances Program, Report to Congress, 2016, roughly two thirds—or 64 percent—of children and youths served by CMHI grantees were living below the federal poverty level.

As one of the four core values of the SOC approach centers on cultural and linguistic competence, practitioners and service providers within the SOC framework must accept, understand, and be responsive to the cultural, racial, and ethnic differences of the families and populations they serve. And the results from the national evaluation indicate they are. According to CMHI’s 2016 report, almost all of the youths and caregivers who responded (96.6 percent and 98.7 percent, respectively) said that they were satisfied with the cultural sensitivity of the services they received. One of CMHI’s goals is therefore to promote the funding of programs that will help build a behavioral health workforce that can effectively implement evidence-based practices that are culturally sensitive and appropriate.

Success and the Future

As stated in its most recent Report to Congress, CMHI is aiming to encourage more and more geographic jurisdictions to adopt the SOC framework, with the ultimate goal of national coverage. But for now, SOC has been implemented and expanded successfully in states such as Maryland, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island. Dr. Gary Blau said that New Jersey is a particularly successful example of how a state can use the SAMHSA grant to expand the SOC framework, in that they “completely changed their system for children’s behavioral health using the system of care approach.”

He also cited Milwaukee, Wisc., as a model of SOC implementation and funding. “They used a wraparound approach and blended funds across child-serving systems in order to provide more coordinated and comprehensive care.”

And Blau expressed confidence that systems of care implementation continues to have a bright future because of support from families and communities across America, from SAMHSA, and from Congress. “Our children and families,” he said, “deserve no less.”

References

That is why, since 1993, SAMHSA’s Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) has been committed to supporting the systems of care (SOC) approach for treating children and youth with serious emotional disturbance (SED) and their families. SOC refers to a coordinated network of home- and community-based services and supports that is also

- Family driven

- Individualized

- Youth guided

- Evidence based

- Culturally and linguistically competent

- Accessible

- Partnership oriented

- Designed to be provided in the least restrictive (i.e., nonfacility based) environment

“A system of care,” said Dr. Gary Blau (pictured above), who serves as CMHS’s Child, Adolescent and Family Branch chief, “is the overarching framework that provides a foundation for what a service array should look like” and represents a “paradigm shift from the one-on-one approach” that has traditionally been used in behavioral healthcare service delivery.

How the System of Care Concept Evolved

The need for developing a less fragmented approach to serving children with behavioral health disorders began in the early 1980s, with the publication of a national study that found that about two thirds of all children and youths with severe emotional disturbances were not receiving appropriate services.2 One reason for this finding, the study pointed out, was the lack of coordination among the various child-serving systems, and the limited resources provided to these children at national, state, and local levels.

In response to this issue, Congress in 1984 provided funding for a comprehensive program, the Child and Adolescent Service System Program, to serve children and youths with SED and their families. A decade later, in the early 1990s, Congress went on to establish the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children with Serious Emotional Disturbances Program, more commonly known as the Children’s Mental Health Initiative (CMHI). Since its inception, CMHI has provided funds for systems of care implementation to more than 300 state, county, territorial, and tribal grantees. CMHI, administered by CMHS, has also continued to receive bipartisan congressional support over the years, with appropriations ranging from $4.9 million in 1993 to $125 million in 2018.

The reason for this continued congressional support, said Blau, is because “there has been a robust national evaluation demonstrating that systems of care work. ” He added, “There are significantly improved clinical outcomes, improvements in school attendance and performance, less involvement in the juvenile justice system, and reductions in suicidal ideation and attempts.”

Why the Systems of Care Approach Works

In CMHI’s most recent Report to Congress,3 which analyzed the cohort of nine demonstration grants initially funded in fiscal year 2010, data were compared for children and youth served by the CMHI grantees at four different time points: a) 6 months before entry into the system of care, b) at intake, and c) at 6 and d) 12 months after intake. Findings from this evaluation showed significant improvements in the children’s overall functioning and that they were less likely to

- Need psychiatric inpatient services

- Visit an emergency room for behavioral or emotional issues

- Be arrested

- Repeat a grade or drop out of school

and

Because SOC is effective in providing community-based services, facilitating meaningful partnerships with families and youths, and focusing on cultural and linguistic needs, the approach can be specifically tailored to the population being served. As Gary Blau said, “what may work in inner-city Chicago, may not work in rural Montana.” He also stressed that SOC helps children across all U.S. populations, including a particular focus on children and youth from minority and underrepresented populations, and on families whose income is below the poverty line.

Why Systems of Care Is

Especially Relevant to the MFP

The systems of care framework is consistent with the both the goals and values of the MFP in its emphasis on serving minority and underserved populations and in stressing the need for building a culturally responsive behavioral health workforce.

CMHI has been successful in providing SOC services to children and youths in populations who experience health disparities, including Hispanics, African Americans, and American Indians or Alaska Natives. For example, as shown in Figure 1, the percentage of black or African American children and youths served through a system of care was more than twice that of the children and youth in the general U.S. population.

In addition, in a 2012 study on American Indian and Alaska Native children and youth, SOC was shown to be effective in reducing rates of suicide attempts.4 Also, as indicated in The Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children With Serious Emotional Disturbances Program, Report to Congress, 2016, roughly two thirds—or 64 percent—of children and youths served by CMHI grantees were living below the federal poverty level.

As one of the four core values of the SOC approach centers on cultural and linguistic competence, practitioners and service providers within the SOC framework must accept, understand, and be responsive to the cultural, racial, and ethnic differences of the families and populations they serve. And the results from the national evaluation indicate they are. According to CMHI’s 2016 report, almost all of the youths and caregivers who responded (96.6 percent and 98.7 percent, respectively) said that they were satisfied with the cultural sensitivity of the services they received. One of CMHI’s goals is therefore to promote the funding of programs that will help build a behavioral health workforce that can effectively implement evidence-based practices that are culturally sensitive and appropriate.

Success and the Future

As stated in its most recent Report to Congress, CMHI is aiming to encourage more and more geographic jurisdictions to adopt the SOC framework, with the ultimate goal of national coverage. But for now, SOC has been implemented and expanded successfully in states such as Maryland, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island. Dr. Gary Blau said that New Jersey is a particularly successful example of how a state can use the SAMHSA grant to expand the SOC framework, in that they “completely changed their system for children’s behavioral health using the system of care approach.”

He also cited Milwaukee, Wisc., as a model of SOC implementation and funding. “They used a wraparound approach and blended funds across child-serving systems in order to provide more coordinated and comprehensive care.”

And Blau expressed confidence that systems of care implementation continues to have a bright future because of support from families and communities across America, from SAMHSA, and from Congress. “Our children and families,” he said, “deserve no less.”

References

1Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013, May 17). Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005–11. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(2): 2–17.

2Knitzer, J., & Olson, L. (1982). Unclaimed children: The failure of public responsibility to children and adolescents in need of mental health services. Washington, D.C.: Children’s Defense Fund.

3Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). The Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children With Serious Emotional Disturbances Program, report to Congress, 2016. Bethesda, Md.: Author.

4Stroul, B., Pires, S., Boyce, S., Krivelyova, A., & Walrath, C. (2014). Return on investment in systems of care for children with behavioral health challenges. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health.

2Knitzer, J., & Olson, L. (1982). Unclaimed children: The failure of public responsibility to children and adolescents in need of mental health services. Washington, D.C.: Children’s Defense Fund.

3Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2016). The Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children With Serious Emotional Disturbances Program, report to Congress, 2016. Bethesda, Md.: Author.

4Stroul, B., Pires, S., Boyce, S., Krivelyova, A., & Walrath, C. (2014). Return on investment in systems of care for children with behavioral health challenges. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health.