BOSTON YOUTHS MAKE CITY'S ENDS MEET

Before we are old enough to vote, we're taught about civic responsibility. Making choices to select our nation's leaders, build better budgets, and improve our schools and communities—we learn early that many fought hard for this right.

But casting a ballot means different things to different people. For some, it is an empowering expression of personal voice. For others, it means little more than fulfilling an obligation.

What it symbolizes to young people is especially significant. When a promise prevails that things can and will change for the better—it just might inspire a lifetime of political engagement.

Participatory Budgeting Fosters Civic Pride

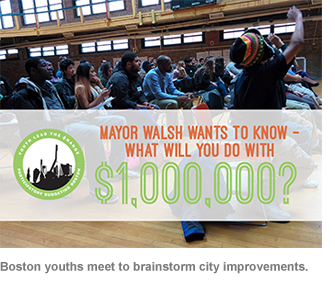

At 26, Shari Davis is one of the youngest city department heads in Boston, Mass., and a fierce supporter of involving young people in local government. She helped Boston lead its first Participatory Budgeting Project (PBP) dedicated entirely to youth, where teens and young adults decided how to spend $1 million of the city's capital funds. From its initiation, the program was youth driven, coordinated, and facilitated.

"We need to stop thinking of a young person as a future leader," says Davis, executive director of Boston's Department of Youth Engagement and Employment. "If we give them tools—if we collaborate—our young leaders can lead today."

"We need to stop thinking of a young person as a future leader," says Davis, executive director of Boston's Department of Youth Engagement and Employment. "If we give them tools—if we collaborate—our young leaders can lead today."

PBP began with the late Mayor Thomas Menino and grew under Mayor Marty Walsh's leadership in a collaboration involving the Mayor's Youth Council, city of Boston, and Boston Centers for Youth and Families. The Council looked at census data to determine where young people lived, and saw which communities were truly marginalized. Though the program targeted residents often excluded from local politics, participatory budgeting was open to all Boston neighborhoods.

For the first time, anyone who wanted a better Boston had a chance to get it. Residents joined listening sessions to voice their concerns in an open, honest way. Though participation was slow to start, interest grew across the city, and by the last meeting there were fewer chairs than attendees.

Program Gains Momentum in First Year

While in its pilot phase, PBP galvanized youths from all parts of Boston. They mulled over the city's needs and generated about 500 bright ideas that were later organized by category. Change agents—a group of young volunteers tasked with proposal writing—reviewed those concepts with the Office of Budget Management, assessing feasibility and impact. Five months later, they were voting on 14 of the best submissions, with residents as young as 12 at the poll.

In the end, seven projects were funded, including several park renovations, community art walls, and Chromebooks for three Boston high schools.

In the end, seven projects were funded, including several park renovations, community art walls, and Chromebooks for three Boston high schools.

"A lot of young people wanted to be involved," says Davis. "But they had to work hard. Teens were writing rules, setting ages [for participation], and determining how and when everyone would vote. They met weekly—and sometimes more—with engineers, park commissioners, and library staff."

Fortunately, the framework for young leadership already stood strong in Boston. City officials have always looked for input from young residents, giving youths a "direct line" to shaping policy, art, culture, and public health and safety.

"By engaging our young people in city government, we are training the next generation of leaders to think critically about how government can better serve our residents," says Mayor Walsh. "I am proud that we will be able to build on past successes in our efforts to increase civic engagement among young people and give them the ability to have a voice in their own future."

"The Mayor's Youth Council model has been around for 20 years," explains Davis, who believes civic engagement can be sparked at a young age. "It has always been an integrated part of city government strategy."

Study Backs PBP's Benefits

Boston's belief that kids connected to a process like PBP will become more politically active is so strong that the city set about proving its hunch. In a survey conducted by Harvard University,1 more than half of those who voted in 2014 said that they would do it again, and many said they would like to participate in more significant ways. Residents cited social benefits, enhanced knowledge and skills, and feeling "empowered" as program benefits. And those directly involved (like steering committee members and change agents) said they developed a broader awareness of other neighborhoods' needs, and a better understanding of government processes and democracy.

"It's always a little jarring to me when I see adults who don't work with young people often," Davis reveals. "They're blown away by the ability and ideas youths have." Through programs like PBP, adults are learning from and collaborating with young people, she adds. "Breaking down stereotypes and barriers has to happen on both sides."

Youth.Boston.gov recently launched a new Web site inviting everyone—in and out of the city—to submit a project idea for PBP's second year. In 2015 the program will have more time to gain momentum and include youth in outreach and marketing. While Boston has a good thing going with participatory budgeting, the city is still learning how best to reach its young people.

Davis sees PBP as a mere microcosm of what youth can do for Boston. "I challenge other city mayors to think about how they involve young people—not just for that quick conversation, but for the long run," she says. "Why not have the experts involved at the table?"

by Carrie Nathans

|

|

|